By Mary Hightower, U of A System Division of Agriculture

The Federal Reserve declined to increase interest rates this week, but any decision to change the interest rate in November may be nixed if the federal government shuts down, said Ryan Loy, extension economist for the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell on Wednesday left open the possibility of an interest rate hike in November or early in 2024, Loy said.

“Come November, they’ll probably raise it, and then the question is whether they’ll raise it again in January,” Loy said, adding that in Wednesday’s updates, “Powell signaled there would be “two ‘quarter’ reductions sometime between Q1 and Q2 next year.”

The Fed Open Market Committee members “looked at their economic projections and said, there’s evidence of inflation, but at the same time consumers are purchasing and our economy is still robust,” Loy said. “Powell did say that he thinks that robust spending’s a good thing. People are going out and buying things, but it shows the rate hikes haven’t had as much of an impact as they thought.”

Loy said Powell is still focused on a “soft landing” for the economy, mindful of the lessons of the “Great Recession” of 2008 and the difficult times of the 1980s.

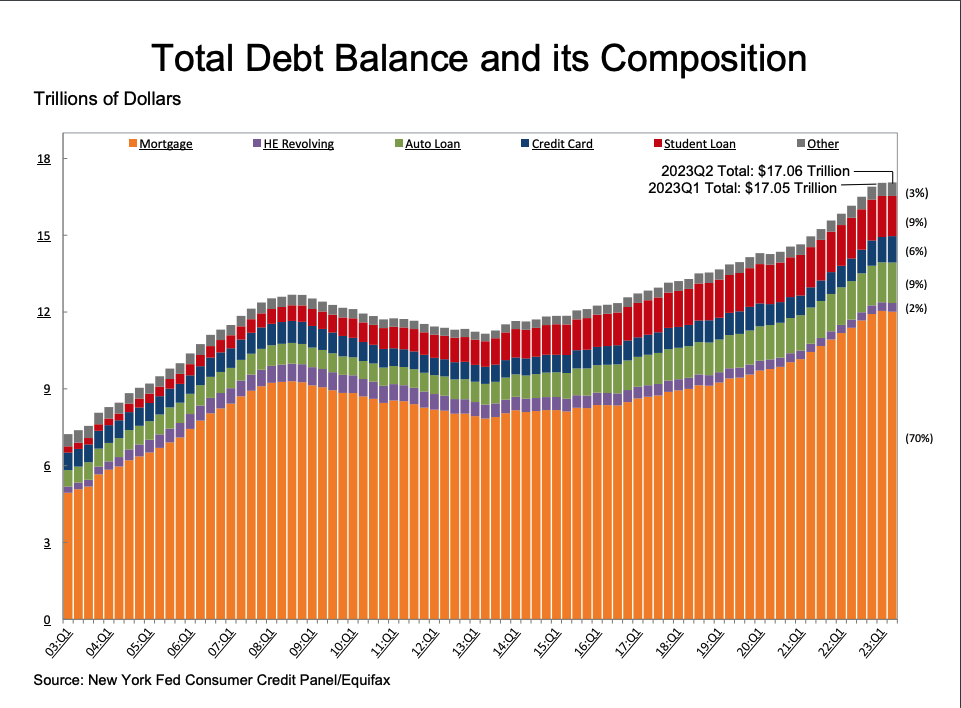

However, the robust consumer spending may be coming at a cost. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, consumer debt is also on the rise. The New York Fed said that in the second quarter of 2023, total household debt grew $16 billion to reach $17.06 trillion. Credit card balances rose $45 billion to a high of $1.03 trillion.

What if there’s a shutdown?

The laws authorizing spending to keep the federal government running will expire Sept. 30. If Congress fails to pass a continuing resolution, or find another means to keep the funds flowing, the federal government will close.

“When a government shutdown happens, nonessential activity just goes out the window, and that includes data collection and dissemination,” Loy said. “Workers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and those sorts of agencies, are going to be told to go home.”

The problem is that the data collected by BLS “is how the Fed bases its monetary policy,” he said.

“If there’s a shutdown for a month and they come to the November meeting, there’s no data then to even decide if a rate hike is necessary,” Loy said. “Powell is going to err on the side of caution and say, something like, ‘if I don’t have any data by that time, then we’re not going to just raise it arbitrarily.’

“Without data, you don’t really know where the economy’s heading for at least a month,” Loy said.

So, why can’t the Fed fund BLS to collect data during the shutdown?

“I even asked this question myself yesterday. In 2019 they had this problem when they shut it down for just a few weeks,” Loy said. While struggling with the debt ceiling problem, “the Fed actually tried to fund these agencies to collect the data so they wouldn’t run into this problem. But was told it was against the will of Congress.”