Daniel Munch | Economist, American Farm Bureau

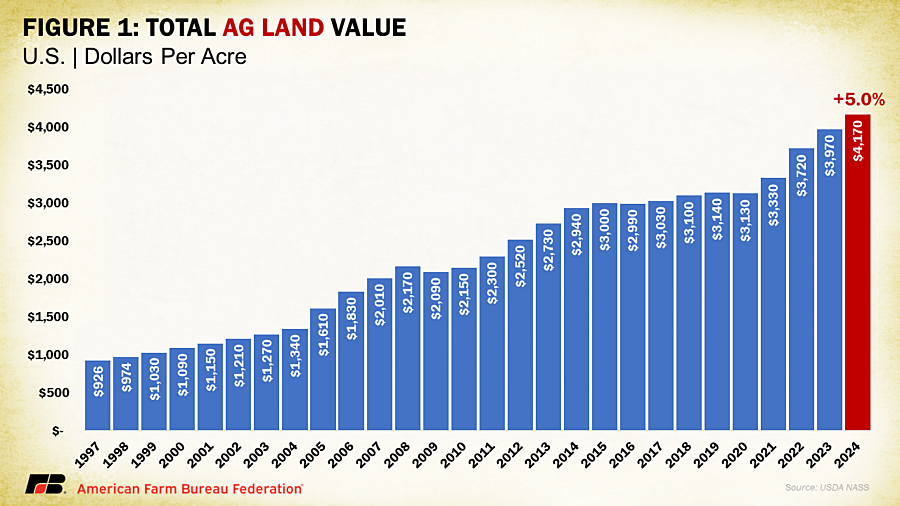

Agricultural land values increased by $200 an acre over last year, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. The Land Values 2024 Summary report, released on August 2, shows a 5% increase to an average $4,170 per acre. This follows a 6.7%, or $250, increase between 2022 and 2023 and marks the fourth consecutive increase in agricultural land values. Cash rent values for cropland were up 3.2% to a record $160 per acre and up 3.3% to $15.50 per acre for pastureland.

This annual report provides one of many indicators of the overall health of the agricultural economy. While record rental rates are an increased production expense for renters, on the flip side, when land values stagnate or decrease, so do collateral values, limiting farmers’ ability to secure loans and access the increased capital needed to acquire higher-cost inputs.

Farm Real Estate Value

The U.S. average farm real estate value, a measurement that includes the value of all land and buildings on farms, clocked in at a record $4,170 per acre. This 5% increase over last year is less than the 6.7% bump between 2022 and 2023 and less than the 11.7% increase between 2021 and 2022, which was the largest change since 2006, when values increased 14% over 2005. The $200 per acre increase from 2023 matches the rise seen between 2020 and 2021, though it falls short of the $250 per acre increase recorded last year and the $390 per acre surge in 2022.

Despite the overall increase in agricultural land values, the rate of growth has decelerated compared to previous years. This deceleration can pose some challenges for farmers. Farmers rely on the equity in their land to finance their operations and investments. Slower growth in land values means slower growth in equity, which can reduce farmers’ ability to leverage their assets for additional capital to purchase inputs like seed and fertilizer. Lenders might perceive a higher risk in lending to farmers, especially if they expect land values to plateau or decrease.

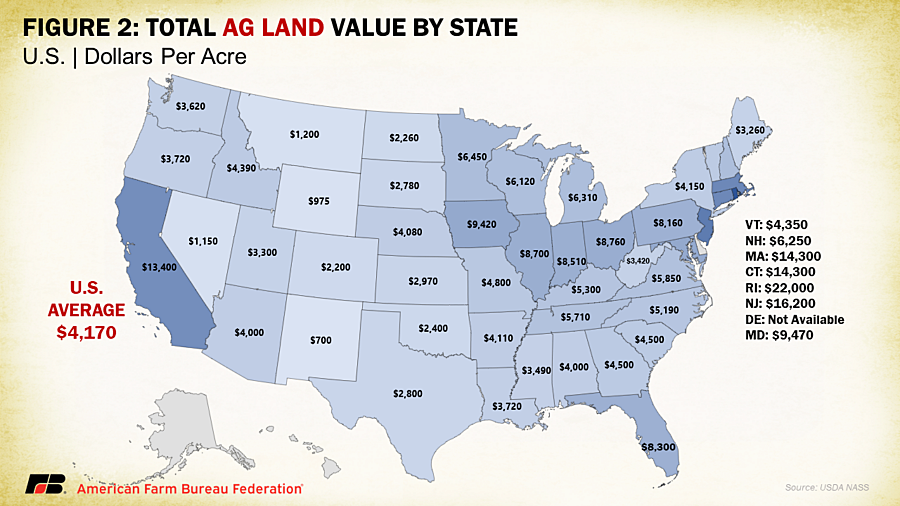

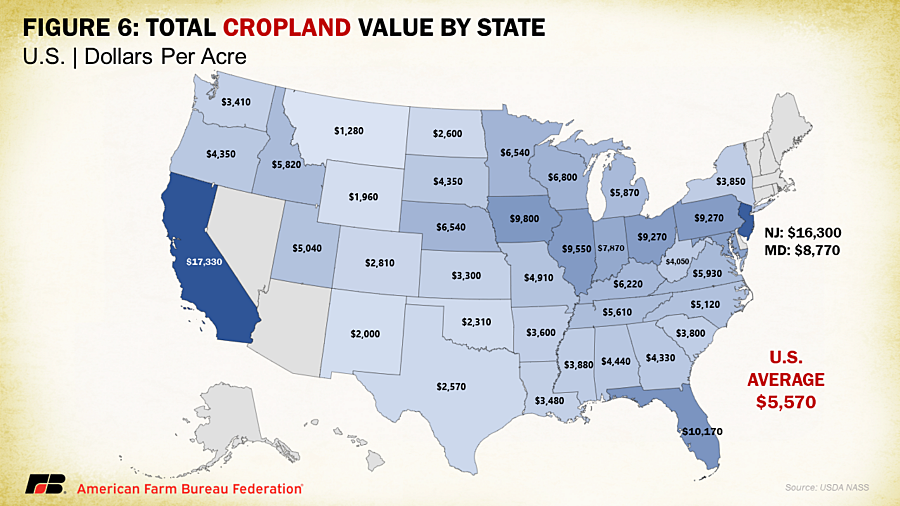

Agricultural land values vary significantly throughout the country, with the highest real estate values concentrated in areas producing high-value crops, such as wine grapes and tree nuts in California. Additionally, areas near urban centers with limited developable land, particularly in Northeast states, experience upward pressure on real estate values from competing uses. Much of the Midwest had higher total comparative agricultural land values, followed by the South and Pacific Northwest, with the Plains and Mountain states experiencing the lowest values.

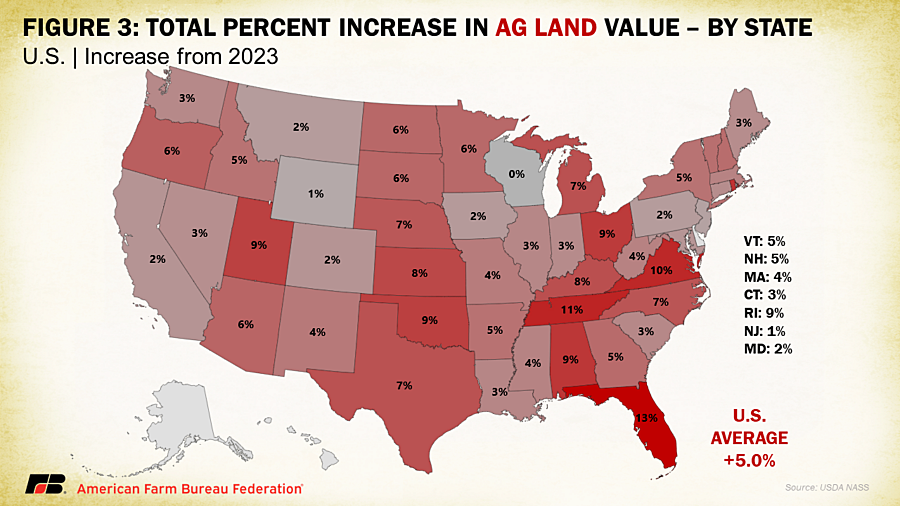

Cropland values typically are based on how profitable farming the land is expected to be in the long-term, so part of this increase can be linked to the lingering effects of high commodity prices in 2021 and 2022, and expectations of the return from productive land in row crop-heavy heartland states. However, this effect has cooled significantly as commodity prices recede. High interest rates have raised the cost of borrowing for farmers, dampening the demand for agricultural land and helping slow the rate of increase in land values as compared to previous years. Government program incentives that provide financial compensation to landowners who voluntarily enroll and retire highly erodible and environmentally sensitive lands, such as those added in 2021 to the Conservation Reserve Program, also contribute to increased competition for active cropland, increasing land prices. Other factors contributing to rising land values are competing land-use interests, which can include urban and suburban sprawl or solar power installations, and increased investment demand for farmland as a safer return on investment during an extended period of inflation. On a state-by-state basis, Florida experienced the largest percent increase (+13%), followed by Tennessee (+11%) and Virginia (+10%). Between 2022 and 2023, five Midwest states experienced double-digit percentage increases in farm real estate values. In this report, only states in the Southeast experienced such increases.

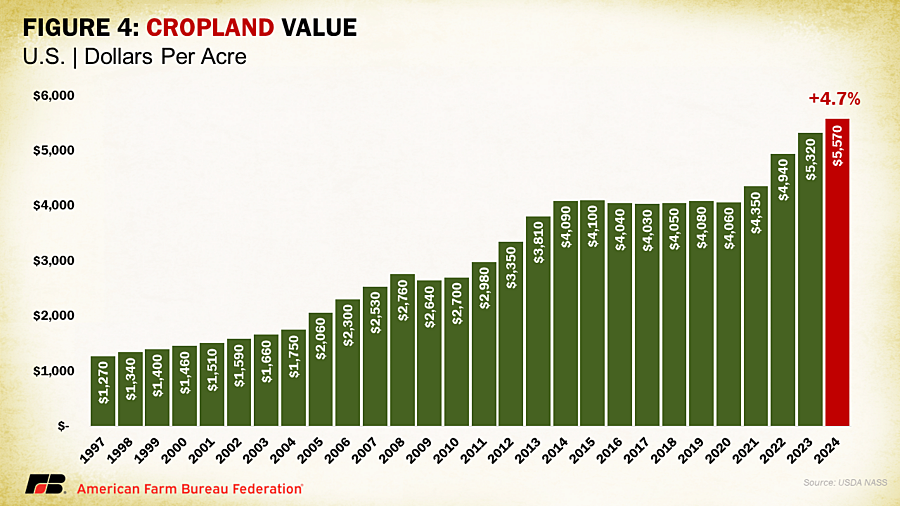

Cropland Value

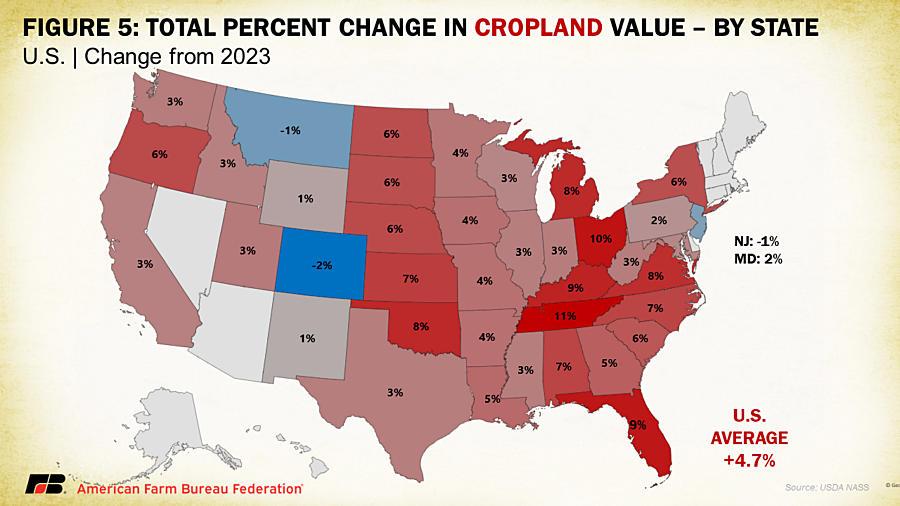

Like overall agricultural real estate values, average U.S. cropland values increased to record levels in 2024, rising to $5,570 per acre. This increase came in as a 4.7% increase over 2023, which is quite a bit less than the 8.1% jump over 2022 and earlier 7.8% increase in cropland values in 2021. In dollar values, this year-over-year increase was $250 per acre, the smallest increase since cropland declined in value between 2019 and 2020. The distribution across the country follows a similar pattern as overall farmland value, with California and the Northeastern states claiming the highest average cropland values. Following that top category is much of the Midwest and Florida, the latter of which has significant acreage of high specialty crop value and residential development pressures. The top four states in terms of percentage growth in cropland values are Tennessee, Ohio, Florida and Kentucky, posting gains of 11%, 10%, 9% and 9%, respectively. This report did show several states with declines in cropland value such as Wyoming (-2%), Montana (-1%) and New Jersey (-1%).

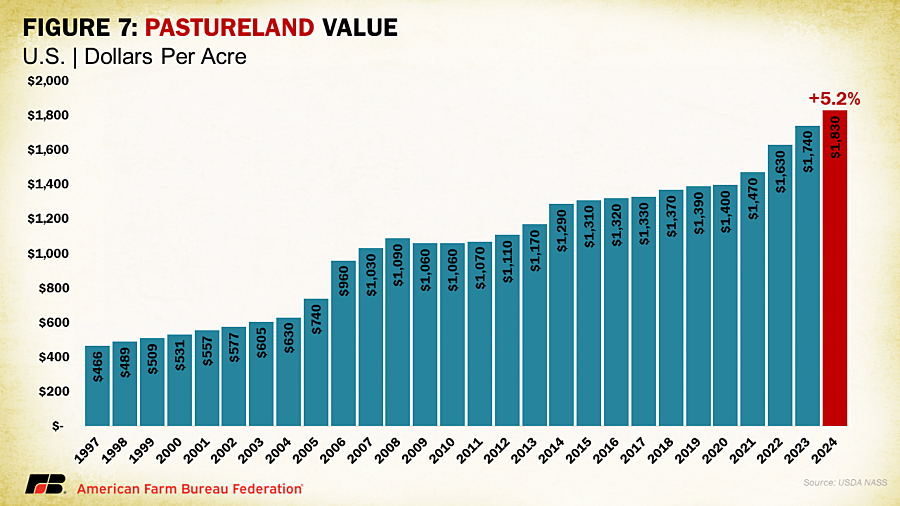

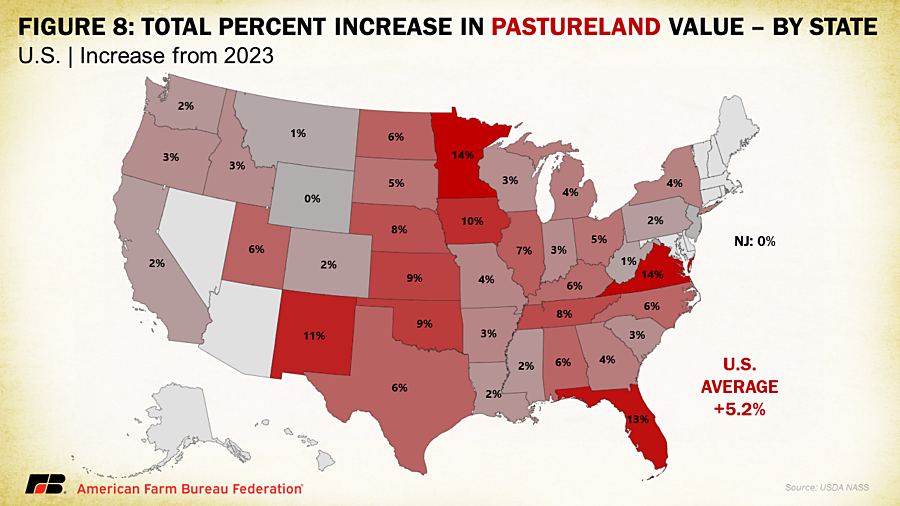

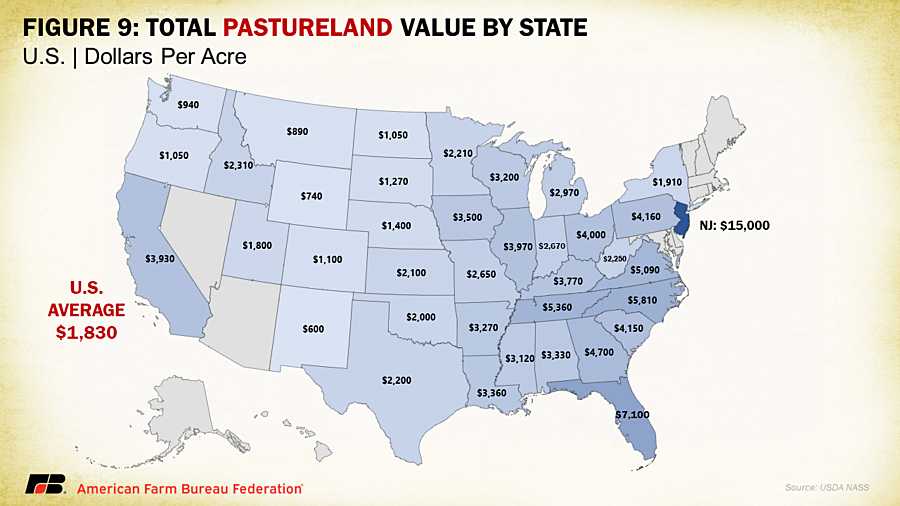

Similar to overall agricultural real estate values and cropland values, pastureland values posted gains from the previous year, coming in at $1,830 per acre on average for the U.S. This is an increase of 5.2% over 2023, a drop from 2023’s 6.7% and 2022’s 11.5%, which followed seven years of little-to-no increases in value. However, the distribution of pastureland values across the country differs from cropland values and real estate values. Instead of the Midwest and California, some of the more valuable pastureland state averages are concentrated along the East Coast and in the mid-South, with the Midwest and the Plains toward the bottom of pastureland values. A very high percentage of grazeable land in the West is owned by the federal government, a portion of which is leased to ranchers using grazing permits. These dynamics limit the role of real estate competition for pastureland in many Western states. States with higher pastureland values tend to be those with higher competition for open land. As has been the case historically, the East Coast states are the most densely populated parts of the country and have correspondingly faced development pressures, resulting in the slicing and dicing of properties at a higher rate than the rest of the country. This results in competition for a small number of plots that can provide adequate grazing features at a much higher cost.

Cash Rent Increases

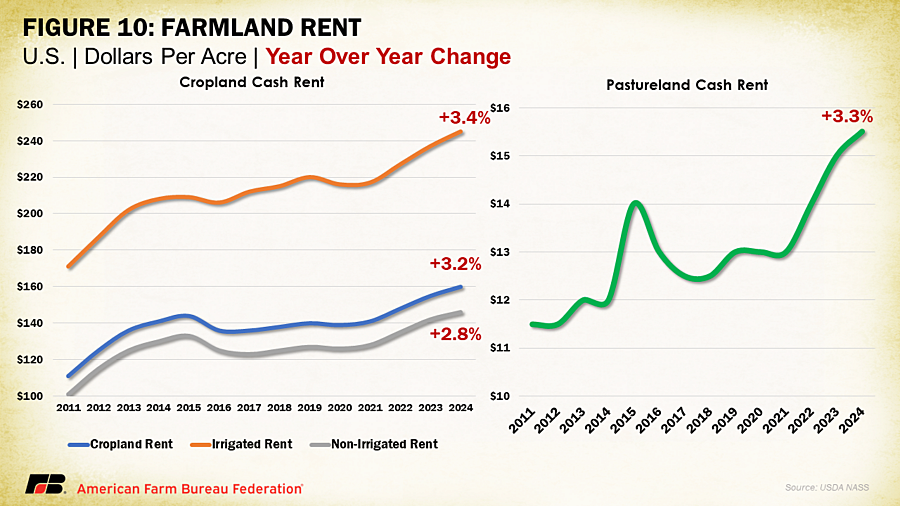

NASS also released data on cash rents, with the increases in land values translating to increases in cash rent. Cash rent tends to be more of a lagging indicator, and likely will be reflected in future producer-landlord negotiations. Average U.S. cropland rent increased to $160 per acre this year, a 3.2% rise over 2023. Irrigated cropland rents increased 3.4% to $245 per acre, while non-irrigated cropland rents increased 2.8% to $146 per acre. Cash rents for pastureland increased 3.3% this year, reaching $15.50 per acre. As pressures on open land intensify across the nation for residential and energy development, leasing cropland becomes less profitable. These trends have been strengthened by some employees’ ability to work at home or away from a central urban office location, which provides people flexibility to work from rural communities and buy properties that compete with agricultural land use. Previously heightened commodity prices that led to larger increases in cash rents have cooled, paralleling the slowing in ag land values more broadly.

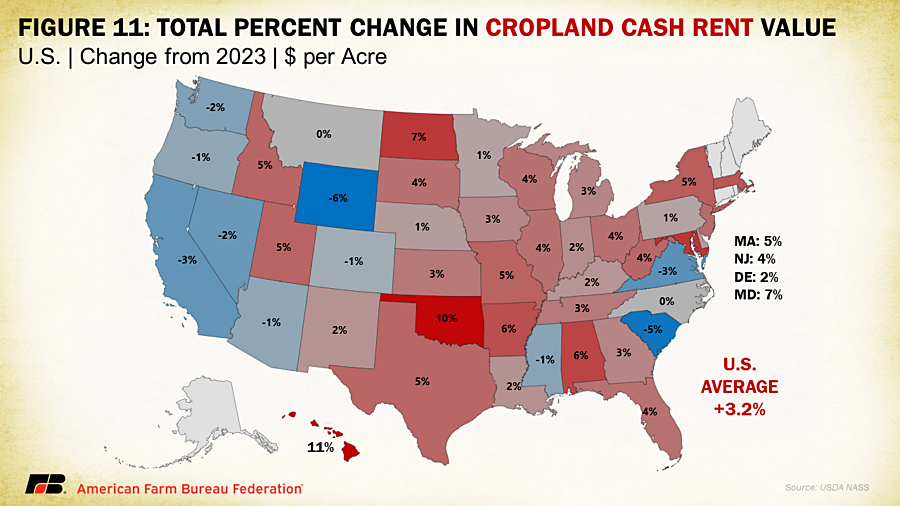

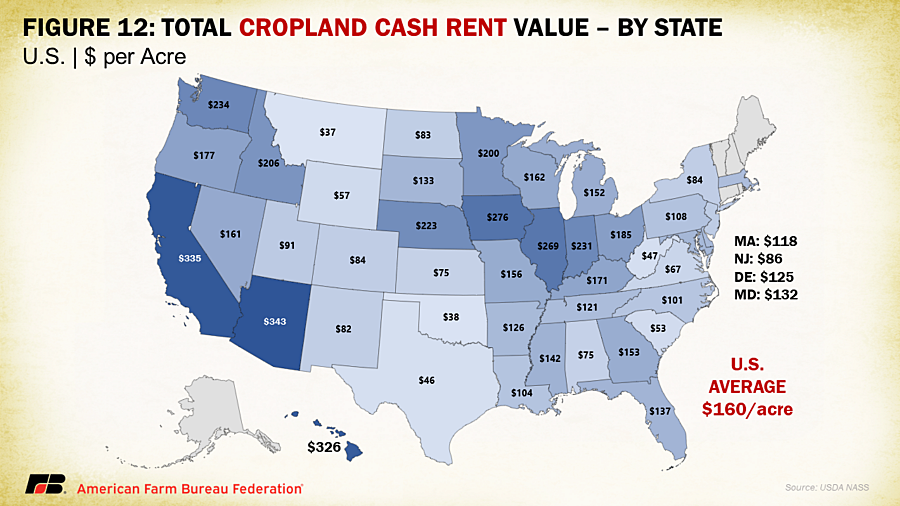

Hawaii and Oklahoma led the country in highest percent increases in cropland cash rental rates in 2024 at 11% and 10%, respectively, followed by North Dakota and Maryland, both at 7%. Decreases in cropland cash rental rates occurred across many Western states, likely a result of improving drought conditions in the region, which has lessened competition for land. By value, the highest cropland rental rates were in Arizona ($343/acre), California ($335/acre) and Hawaii ($326/acre), all states with high-value orchard and specialty crops often linked to water rights that contribute to more valuable contracts. Washington and heartland states of Iowa, Illinois and Indiana made up the next highest cropland rental rate category, linked to higher-value specialty crops for the former and a high density of high-value commodity crops in the latter. Correspondingly, irrigated cropland rent explains the bulk of cropland rental rates in California, Arizona, Washington and other Western states primarily reliant on surface water irrigation, while non-irrigated cropland rent explains that of Midwest states that rely heavily on dryland farming. The access to and cost of water play a large role in regional operating expenses as well as land value costs.

Margins for many producers who rely on rented land are jeopardized by even minimal changes in rental rates. More broadly, those who lack equity from land ownership have reduced access to operating lines of credit needed to fund annual equipment and input purchases; and rising land prices and rents often take away the benefits of high crop prices. In periods of low crop prices, as we are currently experiencing, high rental values pose significant challenges to farmers’ balance sheets, with this year’s income expectations appearing even more dire than originally expected.

Conclusion

USDA’s land value report shows continued increases across the board in agricultural real estate values, cropland values and pastureland values. The average U.S. farm real estate value increased by a $200 per acre, or 5%, over 2023, while the cropland value and pastureland value increased by 4.7% and 5.2%, respectively. Cash rents have also jumped, ranging from 2.8% to 3.4% increases across cropland, irrigated and non-irrigated, and pastureland.

USDA’s Economic Research Service will be releasing updated forecasts for 2024 net farm income on Sept. 5, which will almost certainly show lower returns for most crops in 2024 than were previously projected.

In a continued period of heightened input costs further exacerbated by inflationary pressures, high rent and land costs are yet another hurdle for farmers and ranchers working to produce more crops and raise more livestock. Increases in land values and rents result from rising expectations of higher long-term (nominal) operating profits; and while those increases benefit landowners by enhancing their equity and their rental returns, it also puts farmers on a treadmill, forcing them to cover ever-rising costs for purchased or rented land. Record rental rates are a significant problem for those reliant on renting land and new or beginning farmers. High rental rates and land costs strain their financial viability, particularly when input costs are already high and rising and commodity prices are dropping. The current economic environment highlights the farmers’ call for updates to their safety net in the farm bill to support the continued stability and productivity of the agricultural sector.