Roger Cryan | Chief Economist, American Farm Bureau

On June 27, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) put out a request for information about “Procedures for Quantification, Reporting, and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Associated With the Production of Domestic Agricultural Commodities Used as Biofuel Feedstocks.” What does that mean and why did they do it? On April 30, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced its guidance on how sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) made with corn or soybeans can qualify, under very limited circumstances, for the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Tax Credit. The guidance is the first time that the IRS has outlined a pathway for any grains to be eligible for this credit (often called the Section 40B credit, for its location in the tax code as part of 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act). In December 2023, the IRS put out guidance that provided a similar “safe harbor” for soybean-based fuels that met certain standards under the Environmental Protection Agency’s Renewable Fuel Standard, but this is the first time that grain has clearly qualified.

This guidance is designated a pilot program that will require a very specific bundle of climate-smart agricultural practices to assure the IRS that the corn and soybeans meet the law’s requirement of a 50% greenhouse gas reduction, compared to petroleum-based aviation fuel.

So, What Does This Really Mean for Farmers?

The good news is that this is a first step by the IRS toward recognizing U.S.-grown grains and oilseeds as potential feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuel.

The tax code lays out general eligibility for these credits if the fuel results in 50% less greenhouse gas emissions than petroleum-based fuel; but if the IRS doesn’t agree with how you calculated (or documented) your eligibility, you can be charged with tax fraud and hit with very stiff fines and even jail time. So, complying with IRS guidance can often be the only practical way to safely use such credits.

Ethanol from sugar was already eligible for this credit; but imported ethanol was arguably the only sugar ethanol that is affordable for this, even with the credit. Sugar ethanol eligibility is based on a United Nations climate impact model that considers U.S. corn and soybean production to have a large negative climate impact from land use change – because it generalizes land clearing for row crops in places like Brazil – while it assumes that Brazilian sugar production has limited negative climate impact from land use change because the area devoted to global sugar production has been relatively steady. Imported ethanol also benefits from a relatively low U.S. tariff. As a result, the only SAF plant currently producing jet fuel from ethanol in the United States will claim credits based on its use of Brazilian sugar ethanol.

The April 30 guidance is the first time that any grains have been explicitly included in the Section 40B credit, based on the U.S. Department of Energy’s GREET (Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies) climate model. USDA convinced the IRS to accept a so-called “safe haven” in which very specific sets of cropping practices for corn or soybeans would be assumed to reduce GHG. Specifically, corn growers must have planted a cover crop last fall, planted that corn without tilling, and use a qualifying “enhanced efficiency” fertilizer. Soybean growers must have planted a cover crop last fall and practiced no-till this planting season.

Cover crop decisions, of course, were made last fall, tillage decisions have largely been made, and most fertilizer has already been bought or booked, if not already applied. As of April 28, two days before this pilot program was announced, 27% of corn and 18% of soybeans had already been planted, according to USDA’s crop progress report, so it is too late for farmers to implement these practices if they haven’t already. Those who happened to do what is required for the credit face overwhelming paperwork requirements that dictate very detailed records and documentation of activities that happened months ago, as well as clear segregation of their crop for delivery to the SAF plant.

This credit expires at the end of 2024, so the new guidance will only apply through the 2024 crop year. This means that it may reward a few participants in USDA’s Climate Smart Commodities program, but that no corn or soy farmers will adopt a sustainable practice directly as a result of this guidance, since most of the relevant decisions were made before the rules were known. The requirement for cover-cropping also leaves out many famers whose soil or local climate simply don’t allow for it, and the third-party certification requirements could raise barriers for smaller producers.

USDA’s Search for Better Science

The recent guidance is important for one thing, though: thanks to a hard push by USDA, the Department of Energy has recognized the potential climate benefits of jet fuel from corn within its model and the IRS has accepted at least one narrow set of circumstances under which they can qualify for sustainable fuel credits. It also provides a pathway for soybeans using the GREET model, in addition to the EPA’s RFS standards.

That the IRS calls this a “pilot program” even though it applies to a tax credit that expires at the end of 2024, indicates that they are working on including corn and soybeans more broadly in GREET model validation – and potentially other grains and oilseeds – in the Clean Fuels Production Credit that picks up where this credit leaves off at the end of this year. The so-called Section 45Z credit will apply in 2025 through 2027, and includes sustainable aviation fuel and other fuels.

USDA’s Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) has played a critical in providing the science that has kept the door open – if slightly, to date – for American crops in these tax credit programs.

This brings us back to the OCE’s request for more information from the public on the science of sustainable agriculture. This will help them further demonstrate the wide range of U.S. crops and farming practices that can and should qualify for these tax credits. The due date for input is July 27. This work is critical to making these tax programs work, and to make sure that good work that farmers are doing in support of agricultural sustainability is recognized and rewarded as was intended.

If the guidance for the 45Z credit is also released in late April next year and if it also has very narrowly defined sets of eligible practices, we’ll have roughly the same result: little to no change in practice because it will be too late and too difficult for anyone to respond in 2025.

On the other hand, if the 45Z guidance is published this fall, if it allows for a wider and more flexible range of effective sustainability practices (based on science collected and developed by USDA), and if it has more reasonable recordkeeping requirements, the credit could lead to more sustainable agriculture practices by corn and soybean farmers throughout the country.

SAF Could Be a Big Opportunity for Agriculture

Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack has touted sustainable aviation fuel as one of American agriculture’s greatest potential contributions to climate solutions. The airline industry generates about 2.6% of net greenhouse gas in the U.S., according to the EPA, and airlines around the world are making commitments to reduce or offset these impacts. American agriculture’s opportunity to help in this effort will depend, in part, on whether programs like the Clean Fuels Production Credit recognize the value of corn and soybeans, among other U.S. crops, to reduce these emissions, rather than being displaced by otherwise uneconomical imported biofuel feedstocks that only beat domestic row crops in a narrowly defined scoring system for greenhouse gas reduction.

Many efforts to do good for the environment end up narrowly focused on a single thing; in this case that is greenhouse gas emissions, according to a narrow set of rules.

Some environmental incentives are linked to providing environmental services, with flexibility to simply pay for those services. The renewable fuel standard program sets a standard for ethanol use in gasoline, but allows those who use extra ethanol to sell compliance credits to those who use less. This sort of “offset” can be efficient, providing incentives for a particular benefit without distorting the market overall.

Economic Inefficiencies Undercut Environmental Benefits

Tying the incentive to use of specific products made with specific practices can create a drag on the incentive system and on the economy as a whole. When environmental programs require the actual corn made with sustainable practices be used in the production of a sustainable aviation fuel or when ethanol from Brazil passes ethanol from Iowa on the Atlantic, for two examples, they are causing economic inefficiencies that can undercut the intended environmental benefits. These tax credits allow for flexibility within facilities and even across companies, but this replacement of offsets with “insets: can lead to strange and uneconomic results, and sometimes results that don’t even make environmental sense. One of the keys to sustainability, including sustainable agriculture, is efficiency: producing more with less is sustainable, while producing less with more is a drag on the economy and on the planet.

We already mentioned the example of Brazilian cane sugar-based ethanol, which at times passes U.S.-produced corn ethanol on the high seas on its way to exploit U.S. tax credits that the American product doesn’t qualify for. This U.S. corn ethanol used to pass on its way to Brazil, which was America’s number one ethanol export destination before Brazil imposed heavy tariffs. So now Brazil also grows corn, on cleared rain forest lands, to meet Brazil’s 27% ethanol blending requirement for light-duty vehicles and its sugar ethanol is shipped to the Northern Hemisphere to meet ethanol blending requirements there, in competition with domestic grains.

Used Cooking Oil

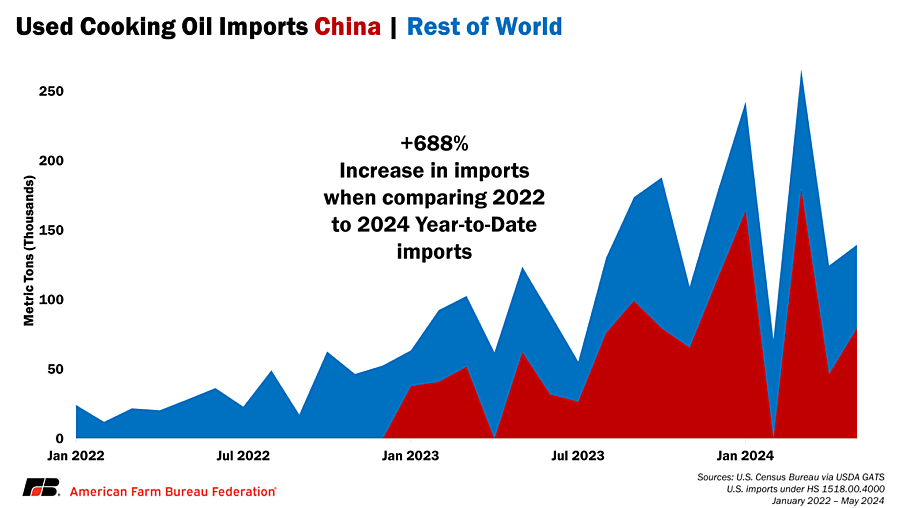

There is also the example of “used cooking oil” , which is being imported into the U.S. in growing volumes. This scores very favorably in climate models, because it is assumed to be a pure waste product of cooking. Like so many former waste products (like whey, cottonseed, apple mash, citrus pulp, almond hulls, bone meal, etc.), the market for used cooking oil was developing nicely, even before the strong government push to promote renewable fuels. And its market price now frequently exceeds that of virgin palm oil because so many government incentives and tax credits are attached to it. The natural economic result is that used cooking oil that could be (and often was) put to perfectly good use in the countries where it comes from, is now being shipped across oceans to harvest tax incentives and government payments. There is also concern that used cooking oil is being blended with virgin oil to create more of the more valuable, and fraudulent, “waste” products. In any case, credits for used cooking oil aren’t doing much to create more sustainable systems, because used cooking oil was already, happily, a market-driven part of the fuel supply.

The risk of this sort of distortion requires some guardrails on the program, if only in the form of a scientific framework that more completely captures the impacts of these shipments.

Conclusion

The tax credit for sustainable aviation fuel was intended to provide the opportunity for American farmers to contribute to greenhouse gas reduction. The 40B tax credit for 2024 mostly missed the mark, except to get the conversation started on providing broader and more flexible eligibility for U.S. row crops, thanks to USDA. More flexible guidance for 45Z credits, provided this fall, could begin to have a real impact, supporting SAF and other renewable fuels made with sustainably produced U.S. grains and oilseeds. Supporting USDA’s efforts to develop a better climate impact model for these crops can, itself, be an important contribution to more sustainable agriculture.